The Evolution of Law and Administration in India: Ancient, Medieval, And Modern

An Introduction to the Legal History of the Subcontinent, essay by Akhi P.

Executive Summary

The evolution of law and administration in India can roughly be divided into three stages: Hindu, Muslim, and British, the last of which continued, with modifications, into modern India. While these terms are not precise, they nonetheless, are useful in understanding the course of Indian history.

During the Hindu period, which lasted from around 1000 BCE to the end of the 12th century CE, there was no single Indian state, despite the growth of a distinct Indian Hindu and Buddhist civilization. India was fragmented politically, socially, and linguistically, enabling the growth of powerful social groups such as village councils, guilds, and castes, who often created their own laws. Alongside this, Hindu beliefs evolved about the role of the state and kings, whose job primarily consisted of the enforcement and protection of the social order and security, rather than the creation of new laws or the transformation of society. Society already had its laws, traditions, and dharma. With states largely confined to military and administrative tasks, a multiplicity of legal schools, commentaries, and traditions arose throughout India, a situation of legal pluralism.

The Indian legal landscape grew even more complex after the 12th century, when large parts of the subcontinent were conquered by Central Asian Muslims, usually of Turkic origin, who introduced Islam and Islamic law into India. Furthermore, as the Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526 CE) and Mughal Empire (1526-1858 CE) expanded and absorbed smaller Hindu and Muslim states, these polities had to devise a framework that could encompass and reconcile the various legal and administrative systems that existed throughout these vast empires. This led to the creation of some administrative and fiscal frameworks that were implemented throughout the region, although religious and familial laws were largely left outside the purview of the state. Nonetheless, the legal system remained complex and heterogeneous, and legal questions often amounted to questions about jurisdiction and choice of law.

The British managed to unite India more thoroughly than the Mughals, and built lasting, modern institutions, which have survived to the present. This required a uniform legal system, achieved through codification and the importation of English common law, with its features of a hierarchy of courts and precedent. However, this Anglo-Indian law incorporated many features of Hindu and Muslim law, and utilized ancient texts in creating precedents. These policies had the effect of simplifying India’s complex legal landscape, making it easier to administer the empire and construct a state. Many of these changes were not resisted by Indians who saw in them a modern system that could be adapted to Indian needs; moreover, the British left many aspects of Hindu and Muslim personal law alone.

Independent India inherited the legal system devised by the British, and combined it with a new constitution that incorporated ideas from Britain as well as other countries. It facilitated the use of the law to effect change by encouraging the state to change society through legislation, a sharp break from India’s past. It also set up a modern state wherein citizens enjoy voting and civil rights on an equal basis as individuals, ideas that were new to a society that was structured on the notion of group identity since antiquity. This is perhaps the only way such as large and diverse state can be held together. Nonetheless, custom and local differences— an enduring characteristic of India, if there is one—remain strong, and there is tension between the formal legal system and customary law and traditions. The aspirations and beliefs of society often differ from the formal law, and identity groups continue to play a large role in government.

Ultimately, both the formal legal system and the customs of the society for which it exists continue to influence each other, and the difference between the two is likely to shrink over time. India’s legal system can most accurately be described at this point as a mixed system with elements of customary, common, and civil law.

The Origins of India’s Unique Socio-Political Characteristics and Hindu Law

The direction of India’s pre-modern political history—and subsequent developments in Indian law and administration—were influenced by religion and geopolitics. The evolution of India’s state system is an intermediate case situated between the European and Chinese models, between Europe’s post-Roman fragmentation into multiple states, and China’s propensity for imperial unity across dynasties. India followed the European pattern up until the 13th century, when larger empires, usually founded by foreigners, appeared.

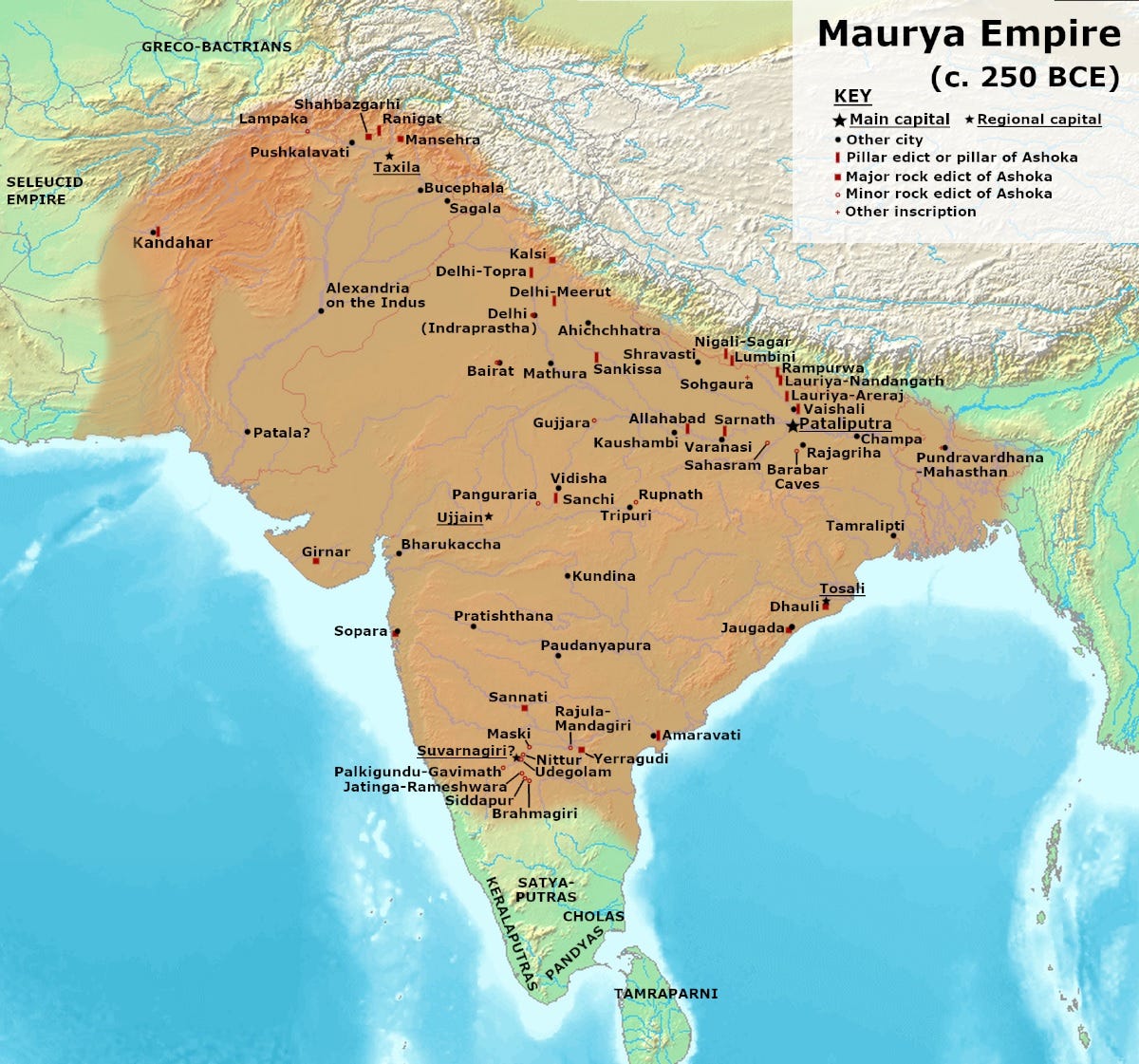

Ancient India, like ancient Greece and ancient Mesopotamia, was home to multiple independent states. In the third century BCE, empires arose in the Mediterranean basin (Rome), India, and China, but only the latter of those would establish a permanent pattern of political unity in its region. In India, the Maurya Empire was established in the aftermath of Alexander the Great’s incursion into the northwestern part of the subcontinent. Lasting for a brief period from between 320 BCE and 185 BCE, it would be the only native Indian state to rule the majority of the subcontinent., Many regional states arose in the subsequent fragmentation of the Maurya Empire, including in the previously pre-state Deccan peninsula in the south, and some of some of foreign origin in the northwest: Persian, Yavana (Greek), Parthian, Kushan, Saka (Scythian), Huna (Hun), and Turushka (Turk).

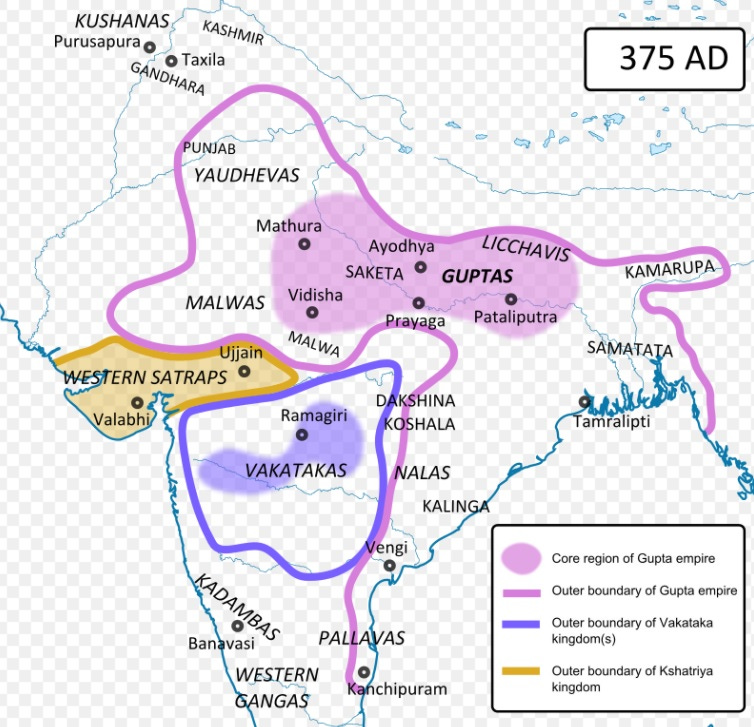

The fragmentation of India into multiple states was partially and temporarily reversed by the emergence of the Gupta Empire in northern India toward the end of the third century of the Common Era. The Gupta Empire united the Ganges valley for the first time since the Maurya Empire and ruled the northern half of the subcontinent until the middle of the sixth century CE. However, the Gupta Empire, and other Indian states of this period were not centralized, bureaucratic states, and many of the functions of the state were outsourced to the local, hereditary elites who had come to dominate the land.

After the Maurya Empire, Indian states “never tried to integrate the political units they conquered into a uniform administrative structure…defeated rulers were left in place to pay tribute and continue the actual governance of their territories.” This inhibited the formation of large empires, and instead supported the creation of myriad long-lived regional states, such as the ones that formed in Europe after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. In his book Escape from Rome, Walter Scheidel describes India’s post-Gupta configuration:

Between the sixth and twelfth centuries, South Asia was divided among regional states that were quite populous in absolute terms but not relative to its total population. Their intermediate size and fairly symmetric interstate competition fostered enhanced military and fiscal capabilities and extended their longevity beyond that of the earlier hegemonic empires. In Lieberman’s view, their ‘increasingly coherent personalities suggest that South Asia may have been headed toward a permanent competitive multistate system not unlike that of Europe.’

One of the most important legacies of the Gupta period was the growth of new movements in what would retroactively become known as Hinduism that strengthened the social position of the priestly and scholarly class responsible—in an era when the sacred and profane were not necessarily distinguished—for much of local administration and law: the Brahmins. The Brahmins would come to enjoy the support of the state throughout most of South and Southeast Asia during this era, as kings emulated their neighbors and sought legitimacy in the rituals and practices of the Brahmins. Consequently, the state in these Indic kingdoms did not need to establish large bureaucracies and engage in much formal lawmaking; administration and law were largely left in the hands of local Brahmins and military and landowning elites such as Rajputs and Thakurs. (Indian society is characterized by the ubiquitous presence of caste, an English word that loosely describes two separate Indic concepts, varna and jati. For further details, see the following excerpt from Akhilesh Pillalamarrri, “Where Did Indians Come From, Part 3: What Is Caste?”, The Diplomat:

Varna, which is what most non-Indians think of as caste is the ‘stratification of all of society into at least four ranks’: the brahmins (priests, intellectuals), kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), vaishyas (merchants, artisans, some farmers), and shudras (laborers), below which are the untouchables or dalits. The stratification is both socioeconomic and ritual: often members of higher castes could not accept cooked food or being touched by members of lower castes (as this would cause ‘ritual pollution’)....The concept of jati is what most Indians mean on the daily level when they refer to caste. It closely resembles the sociological definition of caste, as defined by geneticist David Reich: ‘a group that interacts economically with people outside of it (through specialized economic roles), but segregates itself socially through endogamy (which prevents people from marrying outsiders)’....There are thousands of jati groups or ‘castes’: anywhere between 4,600 and 40,000. ‘Each is assigned a particular rank in the varna system, but strong and complicated endogamy rules prevent people from most jatis from mixing with each other, even if they are of the same varna level… in the past, whole jati groups have changed their varna ranks [by raising their ritual status].

India’s dense population, and the tight networks of “personal loyalty, alliance, and fealty” that came with this density inhibited drastic top-down lawmaking. During the early part of the Common Era:

Land-grants...created administrative pockets in the countryside...in the absence of close supervision by the state, village affairs were now managed by leading local elements, who conducted land transactions without consulting the government…With the innumerable jatis (which were systematized and legalized during this period) governing a large part of the activities of their members, very little was left for central government.

In the Hindu epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, law is conceived as being prior to and distinct from the state, although not entirely independent of it.The Sanskrit word dharma (धर्म) is used to describe the personal and legal duties and obligations of both the ruled and the rulers. This word is variously translated as “duty,” or “righteousness,” and approximates Western concepts ranging from natural law to custom. There is no one dharma, but people can have different dharmas on the basis of their social station, region, and occupation. Throughout most of Indian history, dharma, encompassing the law, was very much the product of local custom and religious scriptures, interpreted and expounded as necessary by Brahmins and village caste leaders, whereas the role of the king and local rulers lay primarily primarily in the enforcement (daṇḍa दण्ड) of criminal sanctions, and of laws and customs, thereby conforming with dharma. Hindu kings who try to change social customs are typically portrayed as wayward in the epics. Thus, in such a society:

The state is subservient to society, especially where social norms and economic transformation are concerned… the ruler has a limited role. He is the guardian and preserver of a social order. It is not the role of the king to transform society. Social change can come only from the religious transformation of individuals….[nonetheless] the king has the authority to levy taxes, provide for the poor and needy, and build infrastructure, but not redistribute property…[the] role of the king has mainly been that of an administrator who must maintain political order while preserving the social order.

Consequently, in modern times, the role of the state and the formal legal system in shaping and changing social norms has been contentious, and both the British Raj and the modern Republic of India have met resistance in doing so. On the other hand, to put a more positive spin on this phenomenon, political scientist Francis Fukuyama points out that rulers in India, in contrast to those in China, were theoretically subject to a higher or independent law, like rulers in the Western and Islamic traditions.

By the beginning of the second millennium CE, India had developed both a diverse array of local states and customs, as well as a common elite culture across the subcontinent. The Hindu law that governed the lives of individuals living in Hindu kingdoms of the time is somewhat of a misnomer: while much of the law was influenced by Brahmins, temples, and Hindu thought, much of the law was also Hindu only in the sense that it was created by Hindus in a Hindu society. It was often of a local or occupational nature, and was not necessarily derived from sacred sources.

Individuals... must have been part of several...corporate bodies simultaneously, such that (1) a guild-weaver might have both (2) a caste and (3) a village affiliation and live on land controlled by (4) a temple or brahmadeya [tax free land gift either in form of single plot or whole villages donated to Brahmins] — each of these imposing its own legal limitations and possibilities…[t]he substance of such laws emerged from within these groups themselves…rulers or appointed judges in turn sometimes adjudicated disputes that arose between the corporate groups or those that for some other reason exceeded the jurisdiction of the group itself. On rarer occasions, rulers imposed their own decrees on a community or region.

Despite the mixed secular and sacred components of the law, temples grew in importance as legal places because they provided the space for various legal, political, and trade professionals to be consolidated in one place. Temples, controlled by Brahmins, were therefore much more important to the functioning of the law than the courts of kings. Various combinations of Brahmins and councils containing guild and caste dignitaries did the work of judges. The king’s decree did have a role in the legal system, but it was not the primary source of law.

These elites also cultivated dharmashastras, or treatises on dharma written in Sanskrit. The dharmashastras would play an important role during the first part of the British period because the British perceived that they were the written religious codes of the Hindu community. The actual nature of these texts were more complex in that they seem to have been generalizations and descriptions of an idealized form of Hindu law without being perspective or legally binding, although appealing to their authority could be legitimizing. The dharmashastras themselves acknowledge as authoritative the various local and occupational laws, with one text noting that “in whichever country, city, village, assembly of learned Brahmins, or town, whatever dharma has been ordained there, one should not abrogate.” Much of the actual content of dharma in practice therefore did not come from treaties on dharma, but from customary law (caritra)., Kings were generally obliged to respect customary laws, generally giving their seal of approval to the decisions of others Nonetheless, some of the content of the dharmashastras did seep into customary law; one particularly influential text was the Manusmriti, the influence of which spread into the Buddhist states of Southeast Asia. For example, the king of Thailand wrote in the preamble to a 1908 penal code that “in the ancient times, the monarchs of the Siamese nation governed their people with laws which were originally derived from the Dhamasustra of Manu, which was then the prevailing law among the inhabitants of India and the neighbouring countries.”

While very little manuscript material survives about the practice of ancient Indian law, there are millions of medieval manuscripts and instruction recording deeds, land grants, debts, contracts, petitions, writs, and many other types of legal decisions, often in vernacular non-Sanskrit languages. Much of this system—complex because it encompasses various jurisdictions in different regions—came to be sidestepped, co-opted, and eventually simplified or jettisoned altogether as the regional independence of India’s kingdoms ended and larger empires came to rule the subcontinent.

The Islamic Period

The tripartite division of Indian history into an ancient (Hindu) era, medieval (Islamic) era, and modern British era was itself a product of British historiography, and not always accurate, as Hindu states survived into the Muslim era, and Hindu and Muslim states into the British period. Nonetheless, the division is useful in understanding the course of Indian history. The Islamic conquests in India ushered in new political, legal, and administrative paradigms, albeit with the incorporation of many pre-Islamic elements.

The pivotal Second Battle of Tarain occurred in 1192 CE, resulting in the defeat of a coalition of Hindu Rajput (warrior) princes by the Ghurid Empire of Afghanistan. Within a few years, the entire Ganges valley—the cultural and demographic heartland of the subcontinent—fell into Muslim hands. This process culminated into the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate in 1206 CE. India had frequently been invaded through the northwest by people coming through Central Asia or Persia; the Islamic conquest was different primarily in that it established, for the first time, states that did not eventually assimilate into Hindu society.

The Delhi Sultanate around 1330 CE

Islamic kingdoms in India faced many of the same problems that Hindu kingdoms did: the difficulty of ruling over such a vast and densely populated land. No sooner did the Delhi Sultanate expand into southern India did large portions of it break away into the Muslim Bahmani sultanate and the Hindu Vijayanagara kingdom, with the governors of Gujarat and Bengal also eventually becoming independent and the Rajput states going their own ways.

However, the Muslim rulers of the larger Indian empires did aim to rule over the entire subcontinent, which over time, did lead to the creation of larger empires in India. India’s political system thus went from being similar to Europe’s to China’s. The most successful Turko-Mongol polity in India was the Mughal Empire. Founded in 1526 CE by the itinerant warrior Babur, descended from both Genghis Khan and Tamurlane, the Mughal Empire grew to include most of the subcontinent by 1700 CE. Large parts of northern India in particular enjoyed the governance of a single state for over two hundred years, although the strain put on the empire by its expansion southward led to the decline of its effective—but not symbolic—authority over its provinces in the 18th century.

India around 1600 CE

One element in the transition of India toward political centralization was ideological. Most of India’s Muslim dynasties were founded by Turkic or Turko-Mongol elites, even though they had all been Persianized—they governed according to the Persian bureaucratic tradition in the Persian language, native to almost nobody in India. In the tradition of the Central Asian conquerors Genghis Khan and Tamulrane, Turkic rulers—Ottoman, Safavid Persian, and Mughal—believed in their divine mandate to rule over as large an empire as possible and aspire towards universal empire., This idea was enhanced by these rulers’ Islamic faith, as they saw their empires as projects meant to bring about the fulfillment of the concept of a universal, boundless ummah, or community in Islamic thought. Another element in this transition was military: northern India’s proximity to the Central Asian steppe enabled horse-mounted warriors to entire the subcontinent and subdue it by the strength of their cavalry. Horses do not thrive in the hot and humid Indian climate, so states that had access to fresh bloodstock had a distinct military advantage. The Mughals were also the first state to deploy gunpowder on a large scale.

Yet, political centralization did not lead to the homogenization of languages, cultures, and legal traditions. Mughal administration was mostly concerned with the extraction of revenue, military levies, and the maintenance of order. “Local customs, traditions, and systems of administration...were not overhauled by the Mughal rulers.” In many ways, Mughal power floated above society rather than penetrating the local level and establishing lasting structures. But while legal pluralism continued, it became more complex during the Muhgal period as different local systems operated with “certain modifications regarding higher appeals and applicability of Islamic laws. As the Mughal Empire grew, what had previously been separate, regional administrative and local jurisdictions came to be connected, at least at the higher levels of the state. The Mughal Emperor, after all, was by 1707 CE the Shahanshāh of Hindustan (شہنشاہ ہندوستان), ruler of India, the highest authority from Kabul to Arcot, near the southern tip of the Deccan peninsula. The emperor’s court mainly exercised appellate jurisdiction and limited original jurisdiction, but was the ultimate authority—in a way, similar to the European conception of the king as the fount of justice. Beneath the emperor’s court was the chief court of the empire, run by a qadi who supervised regional courts, most of which dealt with criminal or Islamic civil cases, and which allowed local village councils to operate with “immense legitimacy.”

Islamic rule in India ushered in both new administrative rules—which applied to the entire population of Muslim-ruled states, including Hindus—and Muslim personal law, sharia, which applied only to Muslims, and was applied in a customary manner to Muslim communities in a way similar to the way Hindu customary laws applied to Hindu communities. Sharia (شَرِيعَة) is a diverse system. Within Sunni Islam, the primary religion of the Mughal elite, there are four schools (madhhab) of legal jurisprudence (fiqh), of which the primary one in South Asia is the Hanafi fiqh. This fiqh was adopted by Turkic rulers in the Ottoman and Mughal empires due to its relative flexibility, allowing for qadis—the judges (trained in the Qur’an and the Hadith or saying of Muhammad) of a sharia court—some discretion in judgements. Much of the Islamic civil law tradition in South Asia was influenced by the Fatawa-i Alamgiri, which was promulgated by the Emperor Aurangzeb in 1675. While often seen by scholars and the British as a code, it was more similar to an American restatement: it was a treatise which compiled legal decisions relating “to matters of personal practice such as marriage, divorce, and prayer” in order to inform judges., The text contained multiple, customary interpretations of Islamic law, which “allowed judges to see a range of ways in which the sharia could be applied, and thus encouraged greater adherence to it.”

Some Mughal emperors administered their empire in the universal, Genghisid tradition, such as Akbar (reigned from 1556-1605 CE). Under the reign of Akbar, his son, and his grandson, there was a “uniform land tax,” which was not in conformity with sharia because Hindus and Muslims were taxed at the same rate. On the other hand, Akbar’s great-grandson Aurangzeb (ruled 1658-1707 CE) reintroduced separate taxes for Hindus and Muslims (jizya), which “led to a higher tax burden on non-Muslims and thus created considerable dislike of Aurangzeb’s economic policy.” These rules were also complex, and there were a number of exemptions, creating “considerable confusion.” Islamic sharia on the other hand, could apply to criminal matters for both Hindus and Muslims. Criminal laws did not differ as sharply between communities, and were less culturally specific as murder, theft, rape, and other crimes were universally criminalized.

Rise of the East India Company

The Mughals, like previous empires in India, were unable to rule the vast expanses of the subcontinent effectively for a long period of time. After the death of the Emperor Aurangzeb, local governors, victories, and rulers became effectively independent throughout large parts of the empire, although acknowledging the emperor in Delhi as the source of their legitimacy. Additionally, large parts of India also fell under the control of the Marathas, a Hindu warrior people from western India, the Kingdom of Mysore, in southern India, and the Sikhs in northwestern India (the Punjab); India was also invaded by the Persians and Afghans during this time.

Various players in 18th century India simultaneously acknowledged the Mughal Emperor as their titular sovereign while also building their own empires and seeking legitimacy on their own terms. For example, the Maratha king Shivaji Bhonsle was crowned as an independent Hindu sovereign (chhatrapati) in 1674, and his heirs and prime ministers ruled both in the name of the Maratha emperor and as agents, though effectively independent, of the Mughal emperor: a complex legal, administrative, and political situation. It was into this world that the British stepped into. The British were neither the first, nor only Europeans in India; the Portuguese, Dutch, French, and even Danish all operated as traders throughout the subcontinent, but only the French and British trading companies would exercise political power.

The modern history of India began with the 1757 Battle of Plassey between the East India Company (EIC) and the Nawab—local ruler—of Bengal, in eastern India. The EIC began as a trading company based primarily out of the outposts of Bombay (Mumbai), Madras (Chennai), and Calcutta (Kolkata). As the Mughal Empire disintegrated, the EIC and the French East India Company built up armies composed mostly of local Indian soldiers (sepoys) in order to protect their outposts. (European-trained sepoys were considered superior soldiers because they were trained using a Prussian-style drill and were a better equipped and more frequently paid professional army in comparison with most Indian armies, which were raised for a time from the local population as needed.)

Soon enough, these armies were used against each other, as well as to support local allies against other local rulers. After EIC noncompliance with the orders of the Nawab of Bengal to cease fortifying Calcatta, Bengali forces overran it in 1756. The company then sent Lieutenant Colonel Robert Clive to relieve Calcutta, which he did, before exceeding his orders by deposing the Nawab at Plassey and installing a more pliable ruler. A further battle at Buxar in 1764 ended with a British victory led by Hector Munro over the combined forces of the Mughal emperor and the nawabs of Awadh and Bengal. This had the effect of placing all three men at the mercy of the British, resulting in the Treaty of Allahabad (1765). As a result of this treaty, the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II (ruled 1760-1806) granted the EIC the diwani—the office of revenue collection—over the provinces of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, giving the Company a “veneer of Mughal legitimacy.” The agreement gave “the EIC the right to tax 20 million people, and generate an estimated revenue of between £2 million and £3 million a year” with which it could enrich its shareholders and fund more conquests. British rule gradually extended over the rest of India in similar circumstances, defeating other powers such as Mysore (1799) and the Marathas (1818). In particular, the Company directly annexed and ruled the hinterlands near Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras, as well as the fertile Ganges valley and Punjab, while retaining local rulers, who signed subsidiary alliances. However, by the 1830s, British officials had stopped acknowledging the Mughal emperor in public, started using English officially in most capacities, and minted their own coins, although the ambiguous legal relationship between the Mughal Empire and the East India Company continued for two more decades.

Interestingly, while the EIC began administering Bengal as an essentially independent actor from this point onward, its legitimacy in doing so derived from its participation in the existing political dispensation of India at the time, differentiating the British conquest of India from the Spanish conquest of Mexico, in which an entirely new legal and administrative system was established by force of arms. The British were only to change how they ran India in a slow and piecemeal fashion. In fact, in 1765, Clive promised on behalf of the Company to govern “agreeably to the rules of Mahomed and the law of the Empire.” The bureaucracy remained staffed with Mughal officials, with the British only taking control at the apex; but with the caveat that the British were “making all the decisions and taking all the revenues.” A contemporary local history, the Riyaz-us-Salatin notes of the British:

[They] have appointed their own district officers, they make assessments and collections of revenue, administer justice, appoint and dismiss collectors and perform other functions of governance. The sway and authority of the English prevails … and their soldiers are quartering themselves everywhere in the dominions of the Nawab, ostensibly as his servants, but acquiring influence over all affairs.

The Company’s regime in India encountered, and contributed, to the situation of legal pluralism then prevalent. The British and French had established their own legal regimes in their towns, allowing locals to live under their own customary laws while also enforcing commercial laws deriving from their home countries (although EIC officials were not permitted to engage in private commerce). The British towns of Madras and Calcutta saw a boom in trade, and were particularly attractive for Indians to live in, as the political situation in India became chaotic in the wake of the Mughal Empire’s slow disintegration., Calcutta’s “legal system, and the availability of a framework of English commercial law and formal commercial contracts, enforceable by the state, all contributed to making it increasingly the destination of choice for merchants and bankers from across Asia.” Calcutta also fostered private enterprise and was known for its lower and more predictable taxes relative to those found in the Nawab’s Bengal and other Indian states. (Ironically, the modern Indian state of West Bengal, where Kolkata is located, enacted policies which drove out most businesses and entrepreneurs, who subsequently relocated to Mumbai.)

British Debates of the Nature of Law in India

It proved difficult for the East India Company to simply perpetuate the preexisting Mughal legal system, and attempts to improve it, or infuse it with English law inevitably changed its nature, especially as more British jurists got involved with the administration of justice. Moreover, the outwardly Islamic framework of the legal system began to wither away as the British employed the services of Brahmins in developing what would become Anglo-Hindu law for the Hindu majority (A fifth to a quarter of the population of British India was Muslim, in addition to smaller Christian, Sikh, Jain, Buddhist, and Zoroastrian (Parsi) minorities.)

As Company rule persisted in Bengal and spread to other parts of India, and as Mughal prestige faded away, the British were left with the question of how to administer their increasingly large empire. By the 1770s, the British were already effectively ruling Bengal, with Warren Hastings becoming the first Governor General of Fort William in Bengal in 1772. British debates revolved around whether to maintain legal pluralism, or to construct a uniform system based on the Common Law. These two overarching streams of thought on administering India remained in tension throughout colonial-era India: whether to govern Indians by their own laws, or to completely introduce English law. Ultimately, the Anglo-Indian legal system developed as a mixture of these two perspectives.

“Orientalists,” administrators, conservatives and Tories generally championed governing Indians through their own laws, or what the British perceived those laws to be. The legal scholar Christian Burset has argued that the Tories supported this position because of its favorable “political-economic consequences,” noting that many Company officials thought that it would be easier to rule Indians through their own laws. Because the main purpose of the Company was exploitation in the form of taxation, “legal pluralism was ideal for such a regime because it inhibited resistance to the Company’s expropriation of Indian wealth by denying colonial subjects the opportunities for redress afforded by English law.” This is certainly plausible, based on the very testimony of company officials. One contemporary source notes that “ [I]f the natives [of India] should be actually endowed with the real cap of liberty in the jury room...there is danger, nay, there is a certainty, that they would make bold to wear it elsewhere; and then, adieu to the English dominion in Bengal.”

On the other hand, Warren Hastings introduced the language of rights in defending his decision to govern Indians by their own laws, stating that “the rights of a great nation in the most essential point of civil liberty [was] the preservation of its own laws.” Hastings may have had started out with mercenary reasons, but his stay in India enhanced his esteem of Indian culture, and he sought to thread the middle ground between retaining local customary law without modification and the wholesale imposition of English law. Hastings “had been a staunch opponent of the imposition of English common law on the people of India and one of the most enthusiastic patrons in the East India Company of indigenous learning, particularly in the field of law...he had encouraged the systematization of different and often conflicting systems of law in India by commissioning some of the first translations into English of ancient Hindu and Muslim legal texts and setting up educational institutions for the teaching of indigenous law.”

Two things may be true; base and ethical motives could both be cited as reasons that many British officials favored governing Indians by their own laws, along with the fact that well into the 19th century, India was legally-speaking, not a British possession, a point made by Hastings who argued that the rights of the Company were “held, countenanced and established by the law, custom and usage of the Mogul empire, and not by the provisions of any British act of parliament hitherto enacted.”

Hastings was later impeached for alleged abuses of power and ruling India in an arbitrary manner in the Parliament of Great Britain, in one of the most famous trials in legal history. (He was acquitted after a lengthy trial lasting from 1787-1795.) Edmund Burke, who led the impeachment prosecution sought to both argue that Hastings was guilty of violating universal morality, and that his administrative policies did not uphold the traditional rights and customs of Indians. This was a rather strange argument to deploy against the individual who successfully prevented the adoption of common law in India, but it may have been driven by politics.

Arrayed against the orientalists, Tories, and Company administrators, was a school of thought—in the spirit of the European Enlightenment—that advocated for universal, uniform laws, championed by Whigs, liberals, and later the Utilitarian views of Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) and the Mills—James (1773-1836) and John Stuart (1806-1873). As per this view, the purpose of governance and law was as a means of preserving local conditions or custom; rather, it could be transformative by reshaping customs and the economy. The Whig writer John Campbell argued that the prerequisite for prosperity were good laws, which would lead to a flourishing society regardless of race or culture. As Jeremy Bentham put it, the lawgiver could find the great outlines of governance to be “the same for every territory, for every race and for every time.”

James Mill, a follower of Bentham, was Scottish philosopher who rose to become the assistant examiner of correspondence at the East India Company. He wrote a highly influential work on India, the History of British India in 1817, despite the fact that he never visited India itself. James Mill believed that Indians needed a rational system of government based on simple and universal principles, without any regards to the customs and traditions of the subcontinent. According to him, “Indian governments represented fully the evils of despotic rule, namely insecurity of property rights due to an imperfect judicial system and arbitrary power in the hands of elites.” The solution to all of India’s problems was good governance and laws, regardless of who governed or created the laws. Mill furthermore expressed skepticism as to whether non-elite Indian peasants really cared for their traditional laws. Mill’s views were questioned not only by Company administrators and Tories, but by Whigs such as Thomas Babington Macaulay, who saw him as a radical who oversimplified political matters. Nonetheless, Macaulay would go on to draft the Indian penal code of 1860, which was based on abstract principles, rather than Indian tradition.

While James Mill’s views were influential in shaping some British policies—for example, Company officials began to more proactively reshape Indian culture after the 1820s by banning sati (a rare practice involving the self-immolation of a widow on her husband’s funeral pyre) and allowing Hindu widows to remarry—on the whole, the British favored a more nuanced and gradual approach to reforming Indian law during the first half the 19th century. This itself was a shift from the initial British position that they were servants and custodians of local rulers with no right to change the law. Many moderate Whigs and Tories ultimately converged on the view that English law would be introduced in certain realms important to the British empire’s prosperity in colonies such as Quebec and Bengal, like commercial law, but not for matters touching more closely upon local custom such as inheritance and family law.

Company officials such as Thomas Munro (1761-1827) and Mountstuart Elphinstone (1779-1859), both Scots, believed in reform, but through Indian institutions, believing that the British should “should concentrate on preserving indigenous institutions, strengthening and protecting them with the final goal of rejuvenating the Indian political system.” Elphinstone pursued a policy of drawing Indians into the government of India, hoping to produce an indigenously-driven reform of Indian governance. Similar views of legal reforming—mixing Western and local ideas—also drove administrative and legal changes in the Ottoman Empire, Persia, the Qing Empire (China), and Japan later in the 19th century.

Anglo-Indian Law: Common Law and Codification

For better or for worse, Warren Hastings’s policy of translating, compiling, and systemizing Hindu and Muslim law under the aegis of British judges and administrators proved to be the starting point of modern Indian law, which was neither left to its own devices, nor replaced in totality by English common law. Even when the British eventually made major reforms to Indian law, it was mostly in the form of codification; for example, a criminal code was introduced instead of the equivalent common law. Nonetheless, many elements of English common law butterested the structure of the Indian legal system—for example, hierarchical precedent in case law and an adversarial trial system. English also remains the primary language of law in India, requiring a class of intermediaries to translate and explain the law to the majority of Indians who do not speak it (local languages have begun to be used in the lower courts).

While certain aspects of English law, such as commercial law, were introduced into the territories governed by the Company, other parts of the law were derived from local laws and customs. This process led to the creation of Anglo-Indian law, which includes both Anglo-Hindu law and Anglo-Muhammad law. The evolution of Anglo-Indian law began in the 1770s when administrators led by Warren Hastings reached for canonical sources in the Hindu and Muslim traditions, such as the dharmashastras, rather than maintaining the administration of local customary law.This made it easier for British judges, as it would have been quite difficult to gain an understanding of customary law in a new country, without command of Sanskrit and Persian. This decision to reach back to canonical sources was also political—though also made in ignorance of the nature of Hindu and Muslim law—as Hastings wanted to fend off the imposition of English law on Indians by demonstrating the existence of a body of written laws that went beyond traditional rules and practices.

Ultimately, however, this created an entirely new form and body of law, once that diverged from the Indian legal tradition, although the texts that were used in British courts were translated by and elucidated by pandits and other local experts. The attitudes of British administrators and judges inevitably reshaped the structure of Indian law because it was desirable “to attain the...object of introducing uniformity in the decisions of the courts,” perceived as being useful in administering a large country such as India. As the Indologist Rosane Rocher writes, “Anglo-Hindu law amounted to an Anglo disposition of Hindu law.” Despite its origins and divergence from traditional legal practices, this law found widespread local acceptance—at least among urban, educated Indians—because of the courts’ consistent enforcement for winners in litigation.

As the 19th century wore on, courts turned to ancient texts less and less, and instead cited prior cases, and a “system of case law came about,” which was self-referencing. Customary law also began to reemerge in decisions because the British had become more familiar with local conditions by this time. Additionally, courts also began to reshape the law as British power grew, a break from custom. By the turn of the 20th century, ancient texts were quoted primarily through prior cases.

However, during this time, the portions of the law that were under the aegis of Anglo-Indian common law was reduced drastically as legislation and codification came to encompass most of Indian law other than family law, or parts of the law not specifically covered by acts. The impetus behind these changes were not necessarily Benthamite or Utilitarian, despite their influence, but grew out of a perceived need to practicality and simplicity, in a “colonial situation, in which a multiplicity of indigienous laws that English legal experts found hard to understand, coeexisted alongside colonial legislation.”

Codification was seen as a remedy to chaos, even if it was resisted in England and the United States. In “Government of India,” a speech delivered in the House of Commons by Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859)—the father of the Indian Penal Code (1860)—Macaulay argued that “judge-made law, where there is an absolute government and a lax morality, where there is no bar and no public, is a curse and a scandal not to be endured.” He “believe[d] that no country ever stood so much in need of a code of laws as India.” This was because:

We have now in our Eastern empire Hindoo law, Mahometan law, Parsee law, English law, perpetually mingling with each other and disturbing each other, varying with the person, varying with the place. In one and the same cause the process and pleadings are in the fashion of one nation, the judgment is according to the laws of another. An issue evolved according to the rules of Westminster, and decided according to those of Benares….The consequence is that in practice the decisions of the tribunals are altogether arbitrary. What is administered is not law, but a kind of rude and capricious equity. I asked an able and excellent judge lately returned from India how one of our Zillah Courts would decide several legal questions of great importance, questions not involving considerations of religion or of caste, mere questions of commercial law. He told me that it was a mere lottery. He knew how he should himself decide them. But he knew nothing more. I asked a most distinguished civil servant of the Company, with reference to the clause in this Bill on the subject of slavery, whether at present, if a dancing girl ran away from her master, the judge would force her to go back. ‘Some judges,’ he said, ‘send a girl back. Others set her at liberty. The whole is a mere matter of chance. Everything depends on the temper of the individual judge.’

However, Macaulay, taking a realistic approach, stopped short of proposing a total overhaul of India law, in the vein of Benthan and Mill, and instead advocated for a codification where reasonable:

We know that respect must be paid to feelings generated by differences of religion, of nation, and of caste. Much, I am persuaded, may be done to assimilate the different systems of law without wounding those feelings. But, whether we assimilate those systems or not, let us ascertain them; let us digest them. We propose no rash innovation; we wish to give no shock to the prejudices of any part of our subjects. Our principle is simply this; uniformity where you can have it: diversity where you must have it; but in all cases certainty.

Macaulay himself went to India to serve on the Supreme Council of India (1834-1838), and drafted and submitted a penal code that applied to the entire population—Indian and British—to the governor-general in 1837. The code itself was based not on any previously existing Indian law, but on a highly redacted version of English criminal law with influences from the French Code Pénal (1810) and Edward Livingston’s code for Louisiana (1824). It was finally enacted in 1860, with some amendments, after decades of resistance from the Company. It took a rebellion to change everything.

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 decisively changed the nature of British rule in India. Originating among Hindu sepoy units in northern India, it constituted the largest threat to the Company’s rule since its inception. Rebel leaders had the support of some local princes and put forth as its figurehead, the last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah II, as the ruler of all of India. The British regained control by 1858 and put the emperor on trial for treason, which raised numerous jurisdictional questions, as the company’s authority to govern in India came from the 1765 Mughal firman (decree), and the Mughal emperors never “renounced their sovereignty over the company.” Perhaps in the light of such absurdities, and the strange phenomenon of a company ruling over a defunct empire, the British Crown assumed the responsibilities of the Company on November 1, 1858 through the Act for the Better Government of India, inaugurating the Empire of India—the British Raj. The position of Governor-General was replaced with Viceroy, and Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India in 1877. Yet, even under the rule of the Crown, India remained jurisdictionally separate from the United Kingdom until its independence in 1947; this is reflected in the fact that it joined the Olympics and League of Nations under its own name before formal independence.

In the aftermath of the rebellion, the establishment of Crown rule, and the expansion of British rule elsewhere, the British Empire entered its high noon in the latter half of the 19th century, and felt more secure in its civilization and power. It therefore had fewer qualms in establishing legal codes for its Indian subjects, although this had to be balanced against careful consideration of native mores, as the British wished to co-opt local elites and to avoid further rebellions. Thus, personal law was left alone, but a code of civil procedure (1859), a penal code (1860), penal procedure (1861), and the Indian Contract Act of 1872 were enacted.

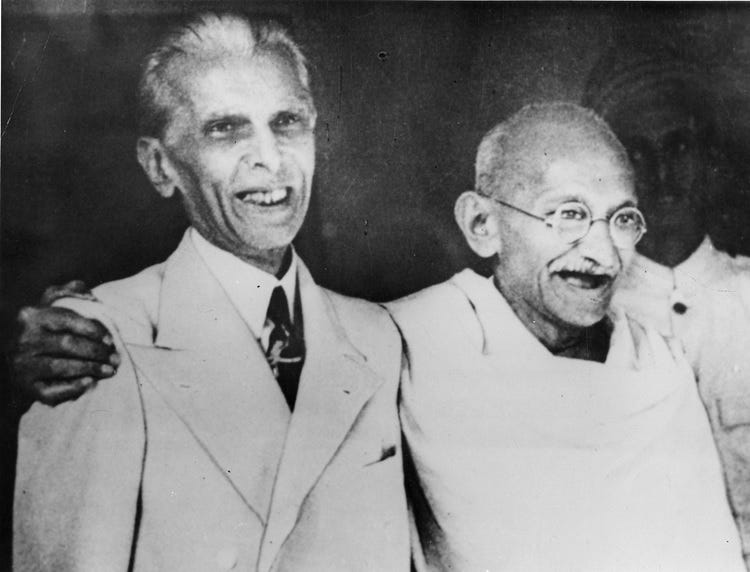

Many contemporary sources in the English-language media criticize the 1860 criminal code, although it was considered progressive at the time. It is often seen as an illiberal colonial hangover, particularly because of its criminalization of sedition, the ease through which the government can curtail protests in the name of security, and its retention of Victorian sexual mores. Yet, no alternative has been proposed beyond amending the law, and it is quite possible to conceive that an India that was never colonized would nonetheless have adopted a legal code, perhaps based on the French or German codes that formed the basis of other codes in Asia, perhaps with some authoritarian attributes. Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948), independent India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964), and Muhammad Ali Jinnah (1876-1948), the founder of Pakistan were all British-trained lawyers. Nehru, in particular, admired the laws that India had inherited from Britain, and wished, in a sharp break from ancient and medieval Indian tradition, to use them to actively reshape and modernize society.

Therefore, the British-era codes were retained in independent India, and were seen as having the nationalistic purpose of strengthening the country, and “for establishing a universal modern regime of power.” This was a reasonable decision, and it did not seem feasible to somehow adopt ancient Indian law to the modern world, rather than use what was already established. Modernity is like a tsunami; one can ride its crest and arrive at a new destination, or go against the flow and be battered into a thousand pieces. Or as the historian Ian Morris put it, “each age gets the thought it needs,” meaning that the legal, political, and ethical systems that predominate in a modern, industrial age will naturally converge with each other on basic principles and differ from those of the agrarian past.

Retrospectively, the colonial-era legal system may have amounted to the best possible balance between a deracinated Indian legal system and the universalizing tendencies of modernity given the circumstances, at least in theory, if not in the particulars. East India Company officials and later the appointees of the Crown were servants of foreign—not Indian—powers, and could hardly have avoided the administrative reforms designed to benefit their employers. Yet, regardless of their actions, it is likely that European legal influence would have spread to India over the course of the 19th century, as non-European powers sought to modernize their legal systems, such as Meiji-era Japan (1868-1912) and the Tanzimat period of reform in the Ottoman Empire (1839-1876).

The British Raj at its Height, 1916. Source: The Project Gutenberg.

The Indian Constitution and Modern Indian Law

The modern, post-independence Indian constitution and modern Indian law grew both out of a need to retain English law as a feature of legal and administrative modernity, and the need to change the law and society top-down through legislation. This is an element of the imperial British Raj’s mode of governance, though not necessarily English law itself, and as a result, India has elements of both European-style civil law, as well as American-style constitutionalism, particularly federalism. Hindu, Muslim, and Christian personal law continue to govern family life, while beyond the institutions of the formal state, traditional and customary practices have endured, especially in rural and tribal areas. Despite governmental attempts to flatten this heterogeneity and transform India, India’s administrative and legal system remains complex.

India’s constitution grew out of the Government of India Act, 1935, which was enacted by the British parliament in response to nationalist Indian agitation for greater Indian participation in government. Two-thirds of the content of India’s post-independence constitution derived from this act. From the end of the 19th century onward, Indian nationalists saw a constitution as an instrument not just for securing their rights as individuals and in relation to the British, but as a means by which a modern nation-state could be built. In this, Indians (and many other non-Westerners such as the Turks, Persians, Malays, and Chinese) looked to the example of Japan and the Meiji Constitution of 1889, which demonstrated how an Asian state could modernize and borrow from Western civilization “without losing their religion and national identity.” Constitutions were a way by which Western legal culture could be synthesized with local traditions in service of strengthening nations politically and militarily in order to safeguard their independence—and establish alternative modernities. Modern India is in many ways an experiment in an alternative modernity, despite using the tools and language of Western political and legal institutions.

The framing of the 1949 Indian constitution is fascinating enough to merit an entire book. Unlike many other postcolonial constitutions, India’s constitution has endured to the present day without a break in continuity due to political turmoil or a coup. Nor was India’s political system copied blindly from any preexisting one—“[It has] been celebrated for the care and deliberation with which it was drafted: Its authors debated its provisions for nearly three years and cast a wide net in their search for sources of inspiration.” For example, B.R. Ambedkar (an ‘untouchable’ leader who studied law in Britain), the chief author of India’s constitution, carefully considered whether to adopt a British-style parliamentary model or a U.S.-style presidential system, before concluding that the former fit better in India’s social circumstances:

Under the non-Parliamentary system, such as the one that exists in the U.S.A., the assessment of the responsibility of the Executive is periodic. It is done by the Electorate. In England, where the Parliamentary system prevails, the assessment of responsibility of the Executive is both daily and periodic. The daily assessment is done by members of Parliament, through questions, Resolutions, No-confidence motions, Adjournment motions and Debates on Addresses. Periodic assessment is done by the Electorate at the time of the election which may take place every five years or earlier. The Daily assessment of responsibility, which is not available under the American system, is, it is felt, far more effective than the periodic assessment and far more necessary in a country like India.

India’s constitution could very accurately be described as an elite project designed to construct a modern nation-state where none previously existed; its purpose was to weld together a country out of a multiplicity of regions, cultures, and religious and linguistic groups. At the time of India’s independence, many Indians did not yet live under a single law. For example, the legal apparatus of the British Raj did not extend to the inhabitants of the princely states, all of which were integrated into India or Pakistan after independence. The state of Travancore, in what is today the southern part of the state of Kerala, maintained its indigenous judicial structure for hundreds of years, only to switch overnight to the British-derived Indian legal system upon its ascension to India in 1949. Hindus, Muslims, and other religious groups also lived under their own personal laws, which were not fully systemized, while some tribal groups lived completely out of the state’s ambit—true even today. Yet, the moment the constitution came into force, every single adult Indian was granted the right to vote and participate in India’s political system as citizens. The caste system was legally abolished—though it persists at the social level—distinction between Indians on the basis of religion were minimized, and women gained the same rights as men.

This led to some top-down change. India’s entire adult population gained the right to vote when the constitution was enacted in 1950. They used their power to buy into the constitutional system, sending representatives to Delhi, and receiving the benefits of contemporary life, however piecemeal and gradual, in return: modernity spread in tandem with electoral democracy, as roads, power plants, and schools were constructed. Development in the form of literacy and electricity and roads is seen as a universal good by Indians. While some customary mores did not change much—for example, today only 5 percent of marriages are inter-caste—the modern, liberal framework of the state did change attitudes toward freedom, equality, and social relations; no Indian party advocates for unequal treatment of castes or the sexes, for example.

Change occurred from the ground up as well: as more Indians began to participate in the formal political system, customary law and mores increasingly found its way into Indian law, often relating to local matters. Legislators also frequently sidestepped judicial precedent altogether through legislation and codes, although the courts do play a major role interpreting the law and the constitution through precedent. The impact of Indian society on the law almost manifested itself in the procedural realm. The jury, widely seen as an implant foreign to India, was abolished in 1973, because the Indian citizenry was seen as emotional and not educated enough to serve on juries. In 2003, the government commissioned a panel to suggest reforms to India’s judicial system. Subsequently, the Malimath Committee submitted a report that suggested that India adopt a European-style inquisitorial system. While this suggestion has not yet come to anything, the current government has expressed some support in revisiting the committee’s report.

The modern Indian constitution and legal system differs from both the much older U.S. constitution, and ancient Indian conceptions of the law and role of state because the state was seen as an instrument to actively remake society by upholding the perceived positive rights of citizens. The Indian state has intervened in shaping the personal, social, and religious customs of its citizens to eradicate what it perceived to be evils, from abolishing the caste system, to forcing temples to change their practices—Hindu temples in India are managed by trusts controlled by state governments. Thus, the state was “seen as the agent of social and economic transformation.” Nonetheless, some pre-colonial ideas current in India such as the existence of village councils—modern day panchayats—and the idea that the ruler was bound to a law outside of his or her will, survived, and perhaps helped India succeed as an electoral democracy.

The activist bent in the Indian law was the product of design. Soon after the constitution came into effect on January 26, 1950, India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru launched a major legislative initiative to create a modern civil code for Hindu family law, aborgating Anglo-Hindu case law. After much opposition, the Hindu code bills were passed in 1955-1956, consolidating and modernizing family law for Hindus, while also flattening regional and jurisprudential differences. At the time, conservative Hindus were the primary opposition to this scheme. In a sign of how successful some of India’s initial legal reforms were, today’s Hindu-right wants to take codification even further, and abolish the personal laws of all religions in favor of a uniform civil code (UCC) that would apply to all citizens regardless of religion.

Yet, there are limits to the activism of the Indian state, partially the result of the relatively conservative society whose members elect the representatives of the state. Indian society remains linked to its past in an unbroken chain, with no disruptive events such as the Cultural Revolution in China. Despite the spread of mass media, schools, and modern conveniences, the state’s reach is not fully felt in villages and remote areas, and customary law still predominates in many spheres of Indian life (one has but to open an Indian newspaper to read about “village diktats” such as a recent case where a village banned cell phones for unmarried women.)

Yet, the activist bent of the Indian judicial system was limited by its reach; customary law predominates in many spheres of Indian life. Indian society’s link to its past is unbroken—there was no Chinese-style cultural revolution. The state’s ability to effect meaningful change is also due to the fact that its administrative, police, and judicial systems are extremely small and backlogged, a legacy of colonial times, where a small staff was needed to administer a colony, not cater to the needs of citizens. In a sense, not much has changed in governance since the Mughal period, where the state hovered over society. But as India becomes more educated and prosperous, it is likely that citizens will demand greater state capacity.

Conclusion

It would not be inaccurate to describe India’s legal system as mixed and sui generis, a distinct hybrid model shaping the lives of a fifth of the world’s population. India’s post-independent leaders were continuing a tradition of nation-building that consciously began with the British, turning a civilization into a nation-state, or as some would have it, a civilizational-state.

The hybrid imperial British system of common-law and codification continues to evolve and indigenize. As it does, the common law nature of the Indian legal system will continue to recede, and India will likely become more of a mixed system with elements of customary, common, and civil law. On one hand, forces that favor modernization, both the secular-left and Hindu-right, favor codification and greater uniformity in their quest to build a strong, modern nation-state. On the other hand, customary law will increasingly find ways to express itself in the Indian legal system by influencing judicial decisions, legislation, and administration. This could be a positive development, as the distance between the state and society would be reduced, as the state and various groups—many of which have become less traditional due to contact with modernity—continue to co-opt each other. A large scale democracy with numerous identity groups bears a resemblance to a traditional Indian village council—with its balance of community leaders representing different caste groups—writ large. Perhaps herein lie some lessons on the management of a pluralistic society for other countries.

Indian legal history is characterized by an extreme heterogeneity, due to its history of social divisions, religious diversity, and the presence of a multitude of states in the subcontinent. The persistence of customary law and in-group quasi-law activity in modern India is the continuation of an ancient tradition, whereby law derives from society, rather than the state. This changed, however, to some extent with the expansion of the Mughal and British empires, which sought to create some uniformity out of the array of laws and legal systems they found in India. The modern Indian state continues this project, often in tension with parallel systems of traditional law. Despite its difficulties, India today has the most homogenous legal system in its history, and through this is gradually becoming a more integrated country, economically, politically, and socially. This itself is a testimony of the power of the law in building a nation.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ahmed, Nizam. Parliaments in South Asia: India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2020.

Asher, Catherine, and Cynthia Talbot. India Before Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Ayers, Alyssa. “Development and the Indian Elections.” Council on Foreign Relations. April 18, 2019.

Ball, Terence. “James Mill.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. November 30, 2005.

Black, Anthony. The History of Islamic Political Thought. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011.

Burset, Christian. Why Didn't the Common Law Follow the Flag? 105 Va. L. Rev. 483 (2019): 483-542.

Chakrabarti, K. “The Gupta Kingdom” in History of Civilizations of Central Asia. France: Unesco, 1992.

Chibber, Pradeep K. and Rahul Verma. Ideology and Identity: The Changing Party Systems of India. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Colley, Linda. The Gun, the Ship, and the Pen: Warfare, Constitutions, and the Making of the Modern World. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2021.

Dalrymple, William. The Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019.

Dalrymple, William. The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi, 1857. London: Bloomsbury, 2006.

Davis, Donald R. “A Historical Overview of Hindu Law,” in Hinduism and Law: An Introduction, ed. Timothy Lubin et al. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Debroy, Bibek (translator). The Mahabharata (10 volumes). Gurgaon: Penguin Books, 2010.

Deepalakshmi, K. “The Malimath Committee’s recommendations on reforms in the criminal justice system in 20 points.” The Hindu. January 17, 2018.

Esposito, John L. The Oxford History of Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Fukuyama, Francis. The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux Books, 2011.

Herzog, Tamar. A Short History of European Law. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018.

Kapoor, Manvi. “Indian high courts, police forces are grossly understaffed.” Quartz India. November 7, 2019.

Kaul, Chandrika. “From Empire to Independence: The British Raj in India 1858-1947.” BBC. March 3, 2011.

Keay, John. India: A History. New York: Grove Press, 2000.

Law, David S. and Mila Versteeg. The Declining Influence of the United States Constitution. 87 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 762 (2012): 762-858.

Legg, Stephen. “An International Anomaly? Sovereignty, the League of Nations and India's Princely Geographies.” Journal of Historical Geography, Volume 43 (2014): 96-110.

Ludden, David. India and South Asia: A Short History. London: Oneworld Publications, 2002.

Macaulay, Thomas Babington. Government of India. Glasgow: Good Press, 1833.

Masao, “Siamese Law: Old and New” in Twentieth Century Impressions of Siam, Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources, with which is Incorporated an Abridged Edition of Twentieth Century Impressions of British Malaya. London: Lloyds Greater Britain Publishing Company, 1908.

Masud, Muhammad Khalid. “Religion and State in Late Mughal India: The Official Status of the Fatawa Alamgiri.” Lums Law Journal.

Michaels, Alex. “The Practice of Classical Hindu Law” in Hinduism and Law: An Introduction, ed. Timothy Lubin et al. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Morris, Ian. Foragers, Farmers, and Fossil Fuels. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Mukherjee, Mithi. “Justice, War, and the Imperium: India and Britain in Edmund Burke's Prosecutorial Speeches in the Impeachment Trial of Warren Hastings.” Law and History Review 23 (2005), 589-630.

Mohan, Vyas. “Gujarat Village Diktat: No Mobile For Unmarried Women.” The Huffington Post. February 19, 2016.

Patra, Atul Chandra. “An Historical Introduction to the Indian Penal Code.” Journal of the Indian Law Institute Vol. 3, No. 3 (July-Sept., 1961): 351-366.

Pillalamarri, Akhilesh. “3 Problems with War and Strategy in Medieval India.” The Diplomat. August 27, 2016.

Pillalamarri, Akhilesh “How the British Ascended in India 200 Years Ago.” The Diplomat. December 8, 2018.

Pillalamarrri, Akhilesh. “Where Did Indians Come From, Part 3: What Is Caste?” The Diplomat. January 14, 2019.

Rachman, Gideon. “China, India and the Rise of the ‘Civilisation State’”. Financial Times, March 4, 2019.

Reddy, Keerthi. “The Jury System in India as British Legal Transplant: A Study.” Supremo Amicus, Vol. 21 (September 2020).

Rocher, Rosane. “The Creation of Anglo-Hindu Law,” in Hinduism and Law: An Introduction, ed. Timothy Lubin et al. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Shrinivasan, Rukmini. “Just 5% of Indian Marriages Are Inter-Caste: Survey.” The Hindu. November 13, 2014.

Singh, Mahendra Pal and Niraj Kumar. The Indian Legal System: An Enquiry. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Scheidel, Walter. Escape from Rome: The Failure of Empire and the Road to Prosperity. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019.

Streusand, Douglas E. Islamic Gunpowder Empires: Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals. Boulder: Westview, 2011.

“Supreme Court refuses to interfere with Haryana law making Hindi as official language of lower courts,” The Economic Times. June 8, 2020.

The Arthashastra. New Delhi: Penguin, 1992.

“War propelled the writing of constitutions,” The Economist. March 27, 2011.

Williams, Rina Verma. “Hindu Law as Personal Law: State and Identity in the Hindu Code Bills Debates, 1952-1956,” in Hinduism and Law: An Introduction, ed. Timothy Lubin et al. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Zastoupil, Lynn. “J. S. Mill and India,” Victorian Studies 32, no. 1 (1988): 31-54.